On January 17, 1927 Charles Joseph Watters first saw the light of day. Attending college at Seton Hall, he made the decision to become a priest and went on to Immaculate Conception Seminary. Ordained on May 30, 1953, he served parishes in Jersey City, Rutherford, Paramus and Cranford, all in New Jersey.

While attending to his priestly duties, Father Watters became a pilot. His longest solo flight was a trip to Argentina. He earned a commercial pilot’s license and an instrument rating. In 1962 he joined the Air Force National Guard in New Jersey. A military tradition ran in his family with his uncle, John J. Doran, a bosun’s mate aboard the USS Marblehead, having been awarded a medal of honor for his courage at Cienfuegos, Cuba on May 11, 1898.

In August 1965 he transferred to the Army as a chaplain. At the age of 38, a remarkably advanced age to be going through that rugged course in my opinion, Father Watters successfully completed Airborne training and joined the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the Sky Soldiers. In June of 1966 Major Watters began a twelve month tour of duty in Vietnam with the 173rd.

Chaplain Watters quickly became a legend in the 173rd. He constantly stayed with units in combat. When a unit he was attached to rotated to the rear, he joined another unit in action. He believed that his role was to be with the fighting units serving the men. Saying mass, joking with the men, giving them spiritual guidance, tending the wounded, Chaplain Watters seemed to be everywhere. PFC Carlos Lozado remembered decades later that when he lacked the money to buy a crib for a new-born daughter Father Watters sought him out and gave him the money. The word quickly spread in “The Herd”, as the 173rd was called, about the priest who didn’t mind risking his life with them, a reputation sealed when Father Watters made a combat jump with the troops during Operation Junction City on February 22, 1967.

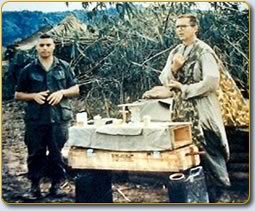

Chaplain Watters became something of a celebrity, but he denigrated the attention paid to him. In May 1967 he told a reporter, “I’m the peaceful kind. All I shoot is my camera. If they start shooting at me, I’d just yell “Tourist!”. Seriously a weapon weighs too much, and, after all, a priest’s job is taking care of the boys. But if we ever get overrun, I guess there’ll be plenty of weapons lying around waiting to be picked up.” During his first tour he was decorated with an Air Medal and a Bronze Star with a V for valor.

In June of 1967 his tour was over and Father Watters was free to leave Vietnam. He didn’t go. Instead he signed up for another tour. His boys needed him, and he couldn’t let them down.

On November 19, 1967, he was with the second battalion, 503 infantry (2/503) as it made ready to assault Hill 875 near Dak To, South Vietnam. Dak To is in Kontum province in the Central Highlands area of Vietnam. Located near the Cambodia and Laos borders, this area was a major infiltration point for North Vietnamese soldiers, supplies and munitions entering South Vietnam from the Ho Chi Minh Trail that wound south from North Vietnam down through Laos and Cambodia. The North Vietnamese high command had built up the North Vietnamese 1st Division in the area around Dak To in October 1967 and decided that the time was ripe to take Dak To. On November 2, 1967 an NVA reconnaissance sergeant surrendered and brought with him a detailed battle plan for the assault on Dak To. Elements of the 1st Cavalry Division and the 173rd Airborne brigade were rushed to Dak To. Beginning on November 4, 1967, American and South Vietnamese units began a series of attacks around Dak To to disrupt the NVA offensive. On November 19, 1967 the 2/503 was ordered to attack and seize Hill 875.

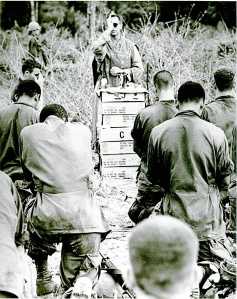

It was thought by Brigadier General Leo H. Schweiter, commanding officer of the 173rd Brigade, that the Hill was held by depleted units of the 66th NVA infantry regiment. That regiment had suffered huge casualties in the earlier fighting around Dak To. Unfortunately the Hill was held by 2000 men of the fresh NVA 174th infantry regiment. The 2/503 had approximately 300 men. Prior to the assault beginning, Father Watters said Mass at the base of the hill, a Mass which was well-attended, with many Protestant troopers joining the Catholic troopers.

The battalion advanced up the north slope of the hill with Delta Company on the left side of the ridge line, Charlie Company on the right side of the ridge line, and Alpha Company in reserve bringing up the rear. Although he could have stayed behind in safety, Chaplain Watters was with the battalion as it advanced. Delta and Charlie quickly came under withering fire from NVA troops in concealed bunkers covered by foliage. Both companies were pinned under heavy enemy fire, including machine guns and mortars as well as rifle fire. Wounded men began crying out for help and Father Watters throughout a very long day rendered that help. Here is the official citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Chaplain Watters distinguished himself during an assault in the vicinity of Dak To. Chaplain Watters was moving with one of the companies when it engaged a heavily armed enemy battalion. As the battle raged and the casualties mounted, Chaplain Watters, with complete disregard for his safety, rushed forward to the line of contact. Unarmed and completely exposed, he moved among, as well as in front of the advancing troops, giving aid to the wounded, assisting in their evacuation, giving words of encouragement, and administering the last rites to the dying. When a wounded paratrooper was standing in shock in front of the assaulting forces, Chaplain Watters ran forward, picked the man up on his shoulders and carried him to safety. As the troopers battled to the first enemy entrenchment, Chaplain Watters ran through the intense enemy fire to the front of the entrenchment to aid a fallen comrade. A short time later, the paratroopers pulled back in preparation for a second assault. Chaplain Watters exposed himself to both friendly and enemy fire between the 2 forces in order to recover 2 wounded soldiers. Later, when the battalion was forced to pull back into a perimeter, Chaplain Watters noticed that several wounded soldiers were lying outside the newly formed perimeter. Without hesitation and ignoring attempts to restrain him, Chaplain Watters left the perimeter three times in the face of small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire to carry and to assist the injured troopers to safety. Satisfied that all of the wounded were inside the perimeter, he began aiding the medics … applying field bandages to open wounds, obtaining and serving food and water, giving spiritual and mental strength and comfort. During his ministering, he moved out to the perimeter from position to position redistributing food and water, and tending to the needs of his men. Chaplain Watters was giving aid to the wounded when he himself was mortally wounded. Chaplain Watters’ unyielding perseverance and selfless devotion to his comrades was in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Army.”

Ironically it was not enemy fire that took the life of Father Watters, but, tragically, an American 500 pound bomb. A Marine pilot, desperately trying to aid the battalion, dropped a bomb which killed 45 Americans, including Father Watters. It was one of the worst friendly fire incidents of the Vietnam War. The official report of the battle is here. Ultimately the 173rd took Hill 875. The NVA units involved in the battles around Dak To were so badly decimated that they were unable to participate in the Tet Offensive at the beginning of 1968.

The many men he had saved that day never forgot Father Watters and neither did the Army. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, one of seven Chaplains to be so honored. The Army on November 20, 2007 renamed the Army Chaplain’s School Watter’s Hall in his honor. His name is on the Vietnam Wall and on the Virtual Wall. Schools have been named after Father Watters, a bridge is being named after him and Assembly 2688 of the Knights of Columbus bears his name. However, I am sure that the honor that means most to Father Watters is that through his efforts some of his boys did not die on Hill 875. Like so many good priests, Father Watters did not view the title of “Father” as a mere honorific, but rather something to live for and, if necessary, die for.